Author Bryan Dickerson asks if The Dark Days of Denim are over?

The state of denim in the surf wear industry is at a crossroads. Is it something where we’re willing to share a collective blind spot, like the petroleom needed to make surfboards? Or will it become the modern equivalent of surf wax wrapped in plastic – once ubiquitous but now heavily frowned upon.

Here we are, the middle of 2020 wondering if The Dark Side of Denim days are over. While a handful of brands are keeping in line with their ethos and stepping up their offerings to meet the demand, others are asking whether such a relatively small segment of their lookbook is worth the expense and effort.

Denim is dirty. And many brands don’t know what to do about it. Most surf companies have a position on sustainable sourcing and their supply chain because it’s bragging rights in an industry that prides itself on being green. But the production of a simple pair of jeans is confusing, complicated and fraught with human and environmental wreckage.

Our favorite surf labels will produce up-cycled, recycled, sustainable boardshorts, wetsuits, hardgoods and even bottle openers – but few have mapped out a plan for jeans. And as these brands expand their denim offerings each season, they are having a hard time deciding how best to keep their green ethos while moving forward into this profitable category rife with eco-transgressions.

Denim is a huge business. Globally it accounted for more than $100 billion in sales in 2017. In Australia ActionWatch estimates the total surf denim market was $12 million AUD that same year. The research, gathered from a panel of participating core specialty store retailers POS systems, found that surf retailers moved an estimated 114,570 units of denim. Stores turned over $18K on average in denim in 2017 accounting for 8.5% of all men’s and women’s apparel sales with the average denim item price point at $73.

The profit for denim is there. But production is not as easy as launching organic cotton T-Shirts or using recycled bottles or coconut husks to make high-performance fabric that then becomes this season’s marquee boardie. The supply chain for a pair of jeans is lengthier, more grueling and ultimately more toxic.

“Kelly said to a reporter before we ever launched a product that we would never make denim,” recalls John Moore, Founder and Chief Creative Officer of Outerknown. “That was because we really didn’t think that we would ever be able to make them up to our sustainability standards. So we actually launched Outerknown saying we would never do denim. Denim is such an integral part of our lifestyle, but the truth is that it’s one of the filthiest manufacturing processes that exists in apparel.”

“Kelly said to a reporter before we ever launched a product that we would never make denim. That was because we really didn’t think that we would ever be able to make them up to our sustainability standards.”– John Moore, Outerknown.

Why is denim so gnarly? First there’s growing the cotton, then picking, then ginning, then spinning, then warp-dyeing, then weaving, then cutting and stitching the damn garment and finally distressing and finishing – with several wash cycles in between. Along the way you have pesticides, herbicides, toxic dyes, chemical runoff, worker issues and finally increased CO2 output. Turning plastic bottles into boardshorts is a walk in the park compared to making a pair of jeans sustainably.

Original dungaree cloth made by Levi Strauss for wagons and tents in the 1870s (and later cut into work jeans by partner Jacob Davis) were derived from a tough fabric made by weavers in Nimes, France who tried to reproduce the famed corduroy of Genoa Italy and failed. In the process they produced fabric that became known as cloth from Nimes or “de Nimes” in French with “jeans” being a mutilation of the Italian city’s name.

Fast forward a century and the laborious production process has, like all things textile, modernized while denim jeans themselves have become as iconic as Elvis’ pompadour. The once excruciatingly difficult production process is now faster and cheaper, but as we keep re-learning, faster and cheaper can be quite expensive in other ways.

For starters cotton is a bitch to grow. The plant needs more water than the average crop, anywhere from 8,000 to 20,000 litres for one plant to grow from seed to harvest. In addition pests love it. One report found that up to 22% of the world’s agricultural insecticides are focused on cotton’s white tufts (which aren’t flowers by the way but pollen tubes similar to the silk found around ears of corn). And much of the crops are treated with Chlorpyrifos, a chemical in the same class as Sarin gas.

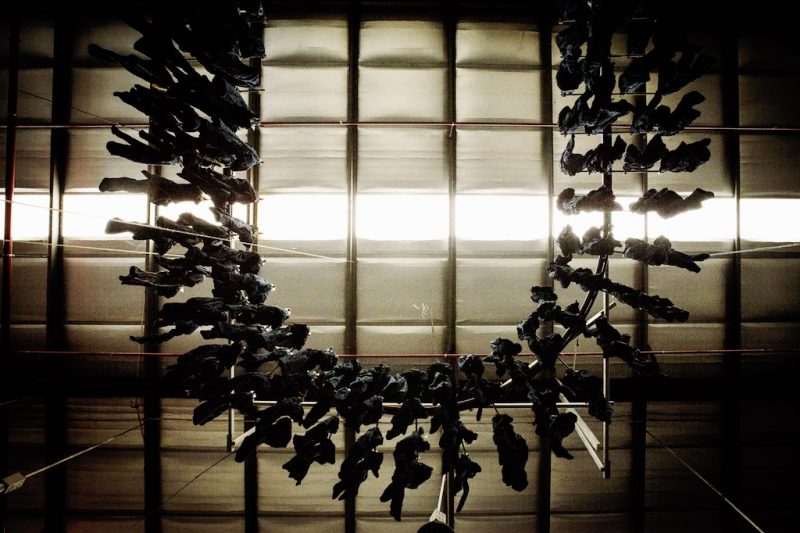

Once the cotton is harvested there’s the extensive energy required to turn it into the tough thread needed for denim. In many countries where denim is made, China and India most notably, the energy intensive process is powered with fossil fuels including coal. Once the material is ready it’s dyed with synthetic indigo in a water-intensive process requiring washing, leaching, dying and more washing. The resulting runoff if untreated – and it is mostly untreated – destroys waterways adjacent to the factories. 56 billion litres of contaminated water produced in Bangledesh go straight into the water supply each year. A blackened foam-covered river runs through Xintang, a place known as “China’s Jeans Town,” which produces more than 200 million pairs of jeans each year.

Greenpeace reported approximately 1.7 million tons of chemicals go into producing roughly two billion pairs of jeans every year. The resulting carbon output is6,000 grams for each pair of denim pants which results in an estimated 2,700,000 metric tons of CO2 each year just from the production of jeans.

The chemical process and runoff is compounded when you factor in distressed jeans – you know, to make them look worn in and faded – which are created through a chemical and labor-intensive process.

And who is making your jeans? In Micha Peled’s documentary “China Blue” there’s footage of workers putting closepins on their eyelids to stay awake to finish their lengthy factory shifts. The Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights (UGF), a German-based nongovernmental organization, found as recently as 2017 that a state-sponsored system of forced labor was still being used in some manufacturing.

So it’s understandable that surf companies are reluctant to jump in and navigate this labyrinth from cotton field-to-retail shelf. At press time Quiksilver, RVCA, Rusty and Billabong didn’t respond to email queries regarding their denim offerings. Hurley’s Evan Slater stated that the company wasn’t doing denim at the present time.

Stokehouse Australia’s General Manager John Mossop said VISSLA offers denim but that they are looking for a more sustainable production model.

“I can not say we have been successful yet, but we are more than keen to explore any of the new sustainability initiatives in denim.” – John Mossop, VISSLA Australia General Manager.

“Our key focus in sustainable apparel has been more focused on key categories such as boardshorts, where we are upcycling waste materials like coconut husks and plastic bottles,” said Mossop. “We also have similar sustainability programs running in categories including walkshorts, wovens and knits. I can not say we have been successful yet, but we are more than keen to explore any of the new sustainability initiatives in denim.”

Denim also doesn’t bring in as much revenue as boardshorts. Surfers will often opt for denim outside of the surf retail sphere while conversely they would never set foot in an H&M store to buy a pair of boardies. So spending company resources on a small category isn’t a priority for many and sustainable goals tend to get focused on the bigger lines.

Mossop confirmed that denim only accounted for a small percentage of the VISSLA lookbook while at Rip Curl, Mimi LaMontagne admitted the same.

“Many of our larger categories feature recycled products, such as our Search Series in Mountainwear” said LaMontagne. “Denim is currently a very small portion of our business, and as it grows we will continue to look into finding ways to become more sustainable in this category.”

Rip Curl, who fatefully discovered that some of its ski gear labeled “Made in China” had actually been made in North Korea, has taken measures to ensure its supply chain is now more transparent. And it’s working. The company received a B+ score on the 2018 Ethical Fashion Report while a handful of the other major surf players scored a C rating.

As it relates to the labor-intensive process of jeans production, Volcom and a handful of others are leading the surf brands, with V-Co having just become a fully accredited member of the Fair Labor Association. To do so the company had to adopt and communicate workplace standards, conduct internal assessments and provide workers with confidential channels to report abuses.

“We are actively addressing our environmental and social impacts with a commitment to responsible manufacturing practices, better fiber sourcing, robust impact evaluation, and meaningful givebacks on a global level,” said Ryan Immegart, Volcom CMO.

When asked if customers are calling more for supply chain transparency or just a “good fit at a good price” Immegart said it varies a lot by customer.

“Depends on the channel, every customer wants it (sustainable denim), but some aren’t willing to pay more for it. We are working tirelessly to bring the most sustainable products to the market at an accessible price point.”

The second largest seller (behind Rusty) of women’s denim to Australia’s core shops is RES Denim who were purchased last year by Lush Productions.

“We monitor our customers feedback and enquiries very closely,” said Hannah Maher, Lush’s Marketing Strategist. “Since acquiring the brand, we have only had one customer enquiry regarding our environmental impact and sustainability practices, so I guess the demand is not high from our customers at this stage.”

Maher added that the company is taking steps to improve their manufacturing processes which includes reevaluating many of their past supplier relationships and production.

“As a business we are environmentally conscious and would like to extend this to our manufacturing processes however remain mindful of the factors that drive us to deliver on quality and a competitive price for our customers.”

Which leads us to the question ofjust how much surfers would pay for a pair of ethical jeans? The sustainability gold standard for sustainability was set by a company from outside of the surf industry – and it comes with a hefty price tag.

Where many companies claim green status by address just one or two steps in the lengthy jean-making process, Dutch company G-Star Raw addresses all of them. They start with 100 percent organic cotton, responsibly and open-sourced denim fabric using natural indigo dye with minimal chemicals and no salts. Then the jeans are made using recycled water in the washing and rinsing process, air dried to save energy, and all sewn together using fair labor practices. The company even produces buttons without toxins. The jeans range in price from $140 to $470AUD. By comparison, a new pair of RVCA jeans will set you back roughly $80AUD.

Most surf brands have shied away from jumping into the sustainable deep end, but a few have embraced the challenge to live up to their sustainable ethos and tackle these issues.

Dane O’Shanassy, Patagonia Director for Australia & New Zealand said more and more customers are demanding to know how their clothes are made and where they come from. As a result Patagonia has gone a step further, insisting on educating their customer base around the materials and processes that go into making their denim products.

“Our sourcing begins with using 100% organic cotton to create the textile,” said O’Shanassy. “A low impact dying process enables us to dramatically reduce water, energy and chemical use and produce less carbon dioxide. We also never distress our denim with harsh chemicals or other methods. Our denim is Fair Trade Certified for sewing.”

But that’s from surfing’s flagship sustainable brand, so it makes sense they’d go the same distance to produce clean denim that they would to make a petroleum-free wetsuit.

U.K. eco-surf brand Finisterre follows Patagonia’s field-to-boutique sustainability model but states they don’t have a “one size fits all” approach to sustainability in denim (or any other category).

“When it comes to denim we make product in the UK and in China,” said Product Director Deborah Luffman. “UK manufacturing suits the organic selvedge and raw denim styles, which require no washing or finishing and suit our UK manufacturer handwriting, however the other organic denim styles are made in China, as the mills and manufacturer have more technical capabilities for dying and finishing denim.”

Finisterre have found that navigating a denim-hungry market that’s slowly evolving its ethos is best done by heading off the chemical and pollution components to jeans manufacturing.

“Our focus is on minimising the use of chemicals and water during the dying stage of denim production, so we don’t believe in distressing, bleaching or deliberately ageing denim,” added Luffman.

“When we do want to achieve a lighter wash we use enzymes, which break down the pigment in the dye, which require less washing, are biodegradable and do not linger in the water supply. Water is the biggest impact from the denim dying production, from both the indigo dying and colour fixing stage of the denim process. All water used from the denim dying and finishing process is passed through on-site filtration treatment and the water is recycled.”

“Other denim washing techniques such as labour intensive stone and bleach require more washes, more power, and often use non-degradable chemicals.”

Huffman said that Finisterre is currently investigating dry-dye and ozone dying, which has the potential to dye and fix denim using no water at all.

For Kelly Slater’s brand Outerknown, the daunting task of doing denim sustainably first came about with some help from the people who basically invented jeans, Levi’s.

Last year Levi’s teamed up with Slater’s brand to create a capsule collection that was start-to-finish sustainable using the jean giant’s Wellthread collection. This subset of Levi’s uses organic cotton, less water, fair labor and a single-fiber strategy that makes the denim clothing article fully recyclable (either reusing the material, or chemically reconstituting it), including buttons, labels and snaps.

Priced at $170-$250 AUD Outerknown’s entry into the sustainable denim market was limited to two jackets and one jean.

But as we went to press Outerknown announced the launch of S.E.A. Jeans with promises that thesupply chain will be totally transparent and the jeans made with 100% organic cotton from the field and follow all pertinent sustainability models. One of the most exciting elements in this development is the factory that will produce the denim as it signals a new textile landscape populated with sustainable denim sources.

“We’re proudly working with Saitex in Vietnam,” said John Moore. “Saitex recycles 98% of the water used in development, and the other 2% is turned into sludge that they can make into building bricks. They also harvest rain water, air dry 85% of their jeans to save energy, and their factory is solar-powered.”

As we move forward and more sustainable options emerge, one sticking point is still consumer habits. Nicky Roswell, Levi’s Marketing Manager for Australia and New Zealand, explained the biggest challenge to sustainable denim in the market place is the consumer’s addiction to fast fashion.

“It’s definitely an ongoing journey in educating consumers not to particpate in the fast fashion (product) cycle and to deliberately choose quality products in favour of a cheaper price point,” said Roswell. “I feel that consumers are starting to become more aware that these principles are all connected, and that’s a good thing for everyone.”

Deborah Luffman at Finisterre agreed, noting other industries like food production are required to have total transparency, but that the clothing industry still has a long way to go.

“The production of clothing is very complex, it involves so many processes, and that can be hard to communicate to the consumer, unlike the food industry which is ahead in explaining how things are made and where things come from,” said Luffman. “There is a lack of transparency from brands resulting in a lack of understanding from consumers; meaning customers are unable to decipher which brands are sustainable and which are just green washing.”

Luffman believes a wave of educated consumers is on their way and will force companies to change.

“Customers are rightly beginning to ask more questions and have an expectation for a brand to walk the talk, and behave as a responsible business, rather than ‘greening’ only an element of their business or product line.”

“Customers are rightly beginning to ask more questions and have an expectation for a brand to walk the talk, and behave as a responsible business, rather than ‘greening’ only an element of their business or product line.” – Deborah Luffman, Finisterre Product Director.

And greenwashing is rampant. Every fast fashion brand has a green or sustainable page on their website regardless of whether they are implementing measures in sustainability or not. From the incredibly vague and non-action oriented GAP proclamation “We perform life cycle assessments to understand environmental impacts for the entire process,” to H&M setting a goal to become climate positive by 2040. In each instance there are no direct supply chain actions toward sustainability.

“I would like to believe all of our fans care deeply about responsible manufacturing practices,” added John Moore. “Let’s be brutally honest, when you are buying something, it has to look really good. Period. So customers are looking at so many factors; the colors, the wash, the fit, the quality and most definitely the price tag. Does it all add up to something they want to buy?”

###