ASB MAGAZINE: NEV HOUSE has won the ASB Greater Good Award at last nights Australian Surfing Awards incorporating the Hall of Fame. Worthy finalists in the category also included The Barney Miller Charity Surf Classic and the Laeticia Brouwer and family, Brouwer Scholarship. The ASB Greater Good Award is Australian Surf Business Magazines major sponsorship with Surfing Australia and is given to the person or group who in the past year has given back to Australian surfing through extraordinary results in a charitable, humanitarian, environmental, or philanthropic cause. Nev’s win in the ASB GREATER GOOD Award also caps a 10-year partnership between Australian Surf Business Magazine and Surfing Australia.

Past winners include Billabong x SurfAid Schools Program (2008), Coastalwatch (2009),David Rastovich/Surfers for Cetaceans (2010), Surf Aid (2011), Barton Lynch (2012), Misfit Aid (2013), National Surfing Reserves (2014), Surfrider Foundation Australia (2015), Andrew McKinnon (2016), Jade Wheatley – Walk for Waves (2017).

In December NevHouse also won the coveted Global Entrepreneur of the Year, awarded by the Royal Family at St James Palace, London (UK). It’s a remarkable achievement for founder Nev Hyman being voted the Global Entrepreneur of The Year from 25,000 registered social enterprises worldwide as part of the HRH Prince Andrew, the Duke of York’s brainchild – Pitch@Palace award.

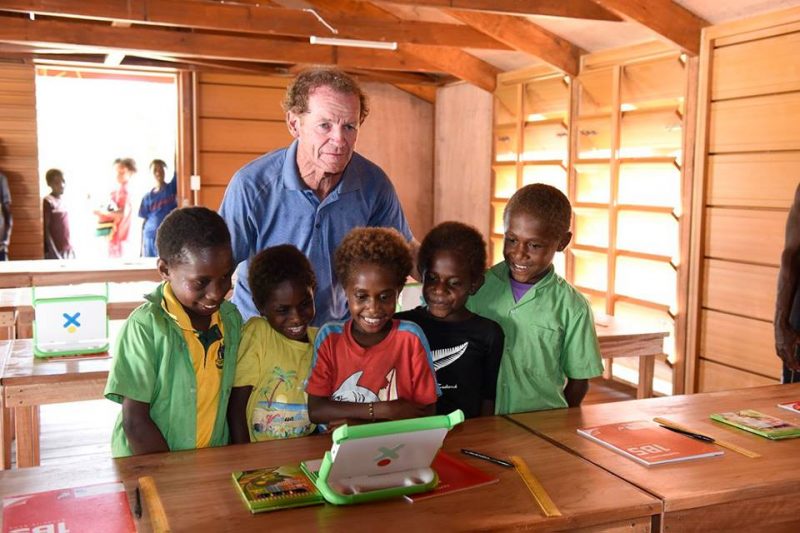

Founded in 2013 by Nev Hyman, NevHouse takes recycled materials and turns it into low cost ‘rapidly deployable’ housing solutions for people who live in slums or no where at all. The company works with foundations, charities, corporate enterprise and government to deliver structures that are built in just a few days and that work on or off the power grid. This means entire communities can be re-built in a short space of time and at an affordable cost. The company is united in its vision of making a positive impact on global housing, education, health, the economy and the environment.

Not content with creating one of Australia’s iconic surfboard brands of the late 20th century, and then pioneering the boards of the 21st century with Firewire, Nev Hyman has embarked on a radical change of direction: sustainable housing.

The NevHouse project aims to use recycled plastic to create prefabricated houses and commercial buildings for use in developing or recovering communities such as Vanuatu, Fiji and remote Australia. In 2016 NevHouse won two awards at the Australian Good Design Awards taking out top honours in both the Sustainability and Architecture categories

The team behind the project comprises Nev Hyman, along with former Red Bull exec Hayden Flier; Queensland Roof works entrepreneur Kacey Bridge, commercial manager Graham Hyman and designer Ken McBryde.

NevHouse had a trial run in Vanuatu in October 2015, creating 41 community structures to aid the recovery from Cyclone Pam, which devastated the remote Enkatalie village on Tanna in March last year. As well as fast deployment, the requirements were that the structures be made from recycled materials and that they could withstand a Category Five cyclone. The designs passed with flying colours and are now set for widespread deployment.

Australasian Surf Business magazine spoke to Nev about the genesis of the project, and just how sustainable housing could be… this story first appeared in #asbmag

*****

Nev Hyman describes the NevHouse project as an example of the random challenges life throws at you.

Back in 2004, he invested in a plastics recycling company, Julien Environmental Technology (JET), purely because he loved the idea of investing in something that’d help clean up the planet. JET took plastics out of the environment and turned them into wood replacement products, an idea that was rare then, but common now.

“Firewire had started out in 2005-6,” Nev Hyman told ASB. “We went through the trauma of developing a new technology, and manufacturing in volume after Taj became so successful on the boards. JET was just a passive investment at first. But then its proprietor passed away and I had to take over because there were anxious investors: it became a necessity to make it work. So a lot of my energy was divided between Firewire and JET.”

Juggling two companies, a GFC and this new technology, Nev had to figure out what to do with JET. “Recycling in developed nations is all smoke and mirrors. Co-mingled waste gets baled up and sent to China, or goes to landfill – it’s not viable to product to take up the waste.

“Recycling in developed nations is all smoke and mirrors. Co-mingled waste gets baled up and sent to China, or goes to landfill – it’s not viable to product to take up the waste.” – Nev Hyman.

“Yet in India, there’s no plastic waste on the streets of Mumbai: kids run ahead of the garbage truck and collect every scrap of it. They’ve got a myriad of products to take up the volume. It’s the same in Indonesia: you have traders in different types of materials. Developing nations have incredible recycling networks already in place.”

The secret to recycling is to develop a product that can be used at the other end. The problem with JET, as Nev saw it, was that everybody likes to see waste taken out of the environment, but the products JET made from it were just shipping pallets, planks and bollards.

“I was sitting in the office in Kuta and a guy says the Indo government have got to build 2000 houses in Lombok. I thought: ‘I can make these out of recycled plastic.’ I went home and engaged engineers and (designer) Ken McBryde. We came up with a design for Indonesia based on the floorplan of a kampong. I developed a 3D plan, showed it off at APEC in 2013, and spoke to the Indonesian government about plastic housing for the poor.”

Nev insists this was all just commercial thinking: “It wasn’t that I set out to be a good bloke,” he told ASB. “It turned out this way. I’m in marketing – surfboards are sexy and easy to sell. This was different.”

“It wasn’t that I set out to be a good bloke. It turned out this way. I’m in marketing – surfboards are sexy and easy to sell. This was different.” – Nev Hyman.

A capital-raising phase then began, and is now almost complete. Nev has spent the last three and a half years developing his concept into reality: selling the dream to investors, building samples, traveling overseas to gauge interest. “I’ve had a great journey overall, but I spent seven months – one of the darkest periods of my life – in Jakarta trying to make this thing happen. I sank most of my own capital into it, divorced and remarried. I put myself and my family under a lot of pressure. So I had to make it happen.”

Nev’s not the first to discover that the wheels of bureaucracy move slowly in Indo – and Jakarta is one of the hardest cities in the world to live in. Leads appear and disappear – meeting businessmen, Ministers. “The carrot was dangled that I’d be meeting Jokowi. Then I accidentally overstayed my visa – I just couldn’t go home: it was a seriously big venture I was chasing. I got Dengue Fever. I was – I don’t mind admitting this – flat broke, just chasing this dream.”

He formed a company in Singapore, and came up with the NevHouse design. Then the cards started to fall his way. “I got jack of Indonesia, went to PNG and chased that, and raised more capital. Then Cyclone Pam hit Vanuatu, and I negotiated with their government; then Kiribati, the Philippines, and so on.

“So we’ve gone through the proof of concept, the proof of delivery, and now we’re setting up a fund in Luxembourg to be a receiving fund, audited and managed independently of us. It’s structured to receive very large sums. There’s lots of money available for this type of solution delivery.”

Each house will take 2-3 tonnes of plastic waste. So NevHouse’s mandate for 40,000 houses in Vanuatu will take up to 120,000 tonnes of waste. And according to Nev, the company is now a preferred supplier of houses in Mexico: “They need 500,000 houses a year,” he told ASB. “Indo needs a million. The size of this market is infinite.”

There’s not enough plastic for all this in the countries where the homes are to be built. “We need to commoditise the waste. So Plan A is to take the plastic waste out of the communities. Then we take the waste from the developed world – for instance I’m negotiating with VISY at the moment. I don’t just want bottles crushed into a square. I want VISY to grind it, pulverise it into particles and send it in bags to Fiji.”

The current NevHouse uses a sustainable wood/plastic composite, which won the Good Design Award. But it only takes one or two polymers out of the environment. To make a new plastic, Nev explained, you need to use the same code of plastic. “But our process will take co-mingled plastic (all seven codes), and you can add to the mix bamboo fibre, coconut husk or sugar cane for tensile strength.” You can even use fly ash, a remnant of industrial incineration.

Version 2 of the NevHouse will use this new process, taking all the plastics out of the environment. And according to Nev, this is not just a developing nation solution – he’s now talking to Byron Bay Shire about affordable housing.

The NevHouses are permanent structures, but can be assembled (and disassembled) in only 2-3 days. “I’ve even spoken to a malaria specialist who talked about adding a repellent compound to the mix, so the house itself permanently repels mozzies.”

In answer to the perennial end-of-life questions, Nev says “Plastic’s not the problem. I love plastic. It’s the improper disposal of plastic that’s the problem. These houses will last a long, long time – multiple generations. That’s the answer. They’re even seismically strong – lightweight and flexible. There’s no concrete in the design, and concrete’s an environmental disaster due to sand mining and the stupid amounts of water it uses. There’s no paint, no render, gyprock or tiles. If it floods you can simply wash it out.

“Plastic’s not the problem. I love plastic. It’s the improper disposal of plastic that’s the problem. These houses will last a long, long time – multiple generations. That’s the answer.” – Nev Hyman.

“It satisfies the Category Five cyclone standard because the houses are built on screw piles. It’s also less flammable than traditional materials, and these codes of plastic are no more toxic when burning than hardwoods – it’s the things inside the house that burn toxically in a fire, not the building material: things like curtains, carpets and electronics. The materials we use are fire retardant, although like anything they will burn eventually.”

After a long discussion, Nev comes closer to admitting there’s some altruism in the NevHouse project. “I want the surf industry to support what I’m doing, but I want to support the surf industry too, for it to get some credit for such initiatives. Like Surf Aid, these communities are surf destinations. I want surfing to help the places we’ve been taking from.”

Visit http://www.nevhouse.com/