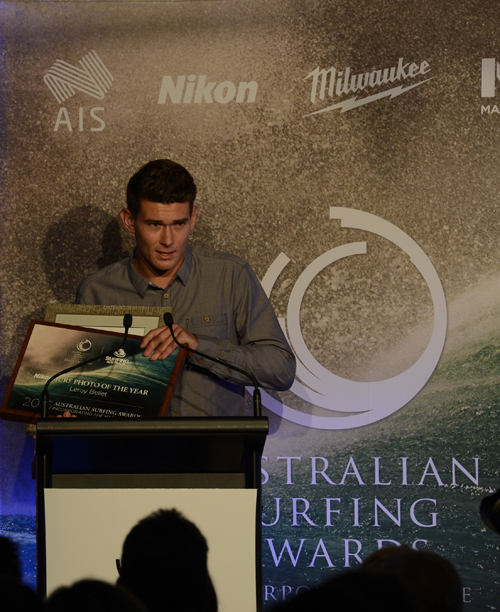

At the 2017 Australian Surfing Hall of Fame Awards I was in the right place at the right time and fortunate enough to eavesdrop on one of the tiny fulcrum moments of surfing history. As (then) seventeen-year-old Leroy Bellet headed for the stage to accept the Nikon Surf Photo of the Year Award, he swept past a white-haired man who simply said ‘Nice Shot Kid’. That man was pioneering Australian surf photographer and film-maker Dick Hoole who was seated right next to me. Dick is a true legend of the lens. He was there at the very genesis of surf photography and surf travel. Future legends of surf film-making like Jack McCoy got their first real break, riding gunshot with Dick when he’d screen classics like ‘Tubular Swells’ and ‘In Search Of Tubular Swells’ as well as ‘A Day In The Life of Wayne Lynch’ I was a kid in the audience at one of these screenings and the impression they left on me has lasted a lifetime. Dick’s muttered words were a masterpiece of understatement, and also a passing of the baton: I knew I’d just witnessed something special and I imagined a future conversation between Leroy and Dick Hoole about the future of surf photography. That conversation first appeared in Australian Surf Business magazine and was written by Jock Serong.

At the 2017 Australian Surfing Hall of Fame Awards I was in the right place at the right time and fortunate enough to eavesdrop on one of the tiny fulcrum moments of surfing history. As (then) seventeen-year-old Leroy Bellet headed for the stage to accept the Nikon Surf Photo of the Year Award, he swept past a white-haired man who simply said ‘Nice Shot Kid’. That man was pioneering Australian surf photographer and film-maker Dick Hoole who was seated right next to me. Dick is a true legend of the lens. He was there at the very genesis of surf photography and surf travel. Future legends of surf film-making like Jack McCoy got their first real break, riding gunshot with Dick when he’d screen classics like ‘Tubular Swells’ and ‘In Search Of Tubular Swells’ as well as ‘A Day In The Life of Wayne Lynch’ I was a kid in the audience at one of these screenings and the impression they left on me has lasted a lifetime. Dick’s muttered words were a masterpiece of understatement, and also a passing of the baton: I knew I’d just witnessed something special and I imagined a future conversation between Leroy and Dick Hoole about the future of surf photography. That conversation first appeared in Australian Surf Business magazine and was written by Jock Serong.

Now, three years in the making, Red Bull have released ‘Chasing The Shot’ which follows Leroy in increasingly dangerous waves, “double-towing” with some of the world’s best surfers inside the barrel with a Nikon, GoPro, and — most spectacularly — a ($100k) Phantom camera, which he promptly destroys.

Leroy Bellet’s award-winning shot was created by tow-surfing with a camera housing and flash, behind a barrelled surfer over a shallow rock-slab.It’s a punishing, low-return technique that has industry legends shaking their heads in disbelief. “He’s 17 years of age,” Dick Hoole told ASB. “How the hell does he have enough talent and experience to nail a shot like that? He should’ve got first, second and third.”

Leroy Bellet’s award-winning shot was created by tow-surfing with a camera housing and flash, behind a barrelled surfer over a shallow rock-slab.It’s a punishing, low-return technique that has industry legends shaking their heads in disbelief. “He’s 17 years of age,” Dick Hoole told ASB. “How the hell does he have enough talent and experience to nail a shot like that? He should’ve got first, second and third.”

Ted Grambeau was equally effusive: “To surf behind the surfer, let alone carrying a camera, is an incredible feat. Those housings with a flash are big, cumbersome things. Think about it: it’s unobtainable for just about everyone on the planet. This is one of the great all-time sports photos, not just in surfing.”

“This is one of the great all-time sports photos, not just in surfing.” – Ted Grambeau

Jon Frank, the inaugural winner of the same award, was also blown away. “The bar’s been raised now by this kid. Technically and physically it’s very demanding: someone my age couldn’t do it.”

The Nikon award has been offered since 2008. Past winners have included Peter ‘Joli’ Wilson and Stuart Gibson. The panel this year included Layne Beachley, ASB’s Keith Curtain, Nick Carroll and Steph Gilmore. Eight of the eleven judges favoured Leroy’s shot over the dozens of other entries. And winning it can literally change lives: two-time winner Ray Collins has said his first win was pivotal towards becoming an internationally recognised surf photographer, and Leroy feels the same way. “The Award was huge for me,” he told ASB.

The pundits are right about the amount of work involved in the shot: it took 260 repetitions to capture Leroy’s award-winning image. “When I surfaced from that wipeout I remember looking down at the back of my housing and just grinning from ear to ear. I’m not the type of person who gets complacent. We jumped back on the rope and kept going.”

Leroy is on record as saying “I want to re-write the rules of the career and I’m willing to do some outrageous things to make that happen.”

“I want to re-write the rules of the career and I’m willing to do some outrageous things to make that happen.” – Leroy Bellet

“I want to re-write the rules of the career and I’m willing to do some outrageous things to make that happen.” – Leroy Bellet

We put that notion to the test with the veterans: can Leroy make a career out of it? “It’s all about monetising eyeballs,” Dick told us. “How do you make money out of something people can see for free? My advice: don’t put em up online! Own it.”

Ted Grambeau agrees. “He’s put himself in a very difficult position now. He can only go bigger and that’s super dangerous, the risk of being hit by the housing, the board, the reef.”

Despite being a fan of the image, Jon Frank is more circumspect about surf photography careers. “The reality is that the people who put everything into gathering the images and words, who document the experience of surfing, they’re the ones who end up going mad, getting divorced. There’s exceptions – some possess the rare combination of a strong business mind and a creative mind – but they’re quite rare. It’s a great job when you’re young – if you can make it work.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Leroy agrees with Jon. “I’m not saying this is sustainable long term as a career. I know it has been in the past, and it could be in the future, but it’s all trial and error.”

Where Leroy has an edge is in his willingness to be commercial. “I’ll split my expenses: a sponsor, a brand like a surfer has; and a magazine to partner with,” he told us. “It’s good, I think, to have more than one source of income. It’s hard in the surf industry to find something reliable.” Think about that last statement and your own level of insight about income stability at seventeen.

But Leroy has a unique selling point. “It’s a great benefit to be both an athlete and a technical person. It all depends on me not hurting myself.” That sounds sensible. So what did he mean by being “willing to do outrageous things”? “To be intentionally wiping out on a wave of consequence is mentally hard. You might be bleeding, bruised, gasping for air and it’s exhausting to come up and go ‘yep, let’s go again’.”

Ted Grambeau gets angry that this level of commitment and skill isn’t better rewarded. “I’ve been lucky enough to make a living from this, (but) it’s almost sad he’s throwing such talent at the poorest of industries. If he was in fashion he’d be justifiably compensated.

“Kids are producing amazing water photos every day, things that the best sports photographers in the world can’t shoot. It’s a tiny domain. But we’ve settled for the free trip and the T-shirt. Our idea of negotiating is: ‘Can I have twoT-shirts?’ The market has been saturated by the instant gratification of Instagram. As a result, 99.9% of photos don’t earn a cent.”

“The market has been saturated by the instant gratification of Instagram. As a result, 99.9% of photos don’t earn a cent.” – Ted Grambeau

Ted’s advice to Leroy sounds much like Dick Hoole’s, “You’ve got unique content, and that’s where the value lies today. Put a value on it. Maybe that means not selling it for a while. You’re going to break bones, break cameras and equipment. Shouldn’t you be compensated accordingly?”

“Sometimes I’m really concerned for his welfare,” said his tow partner Brett Burcher. “He puts himself through torture, testing angles and equipment with no end result. One particular day, he must have stuffed himself inside twenty tubes, only to return to shore with water beads covering every photo. He stuck to his guns, learned from his mistakes.”

“I think I’ve learned a lot from what I’ve done so far,” Leroy reflected at the conclusion of our interview. “I have to do everything for a reason. I don’t like to waste time. The map of this digital media landscape is as blurry to me at my age as it is to Jon Frank or Ted Grambeau at their ages. None of us know what’s next. But I do know that the people who’ve made a career of it deserve their success.”

Plainly there is a common thread across Greenough, Merkel, Hoole and Crawford, to Grambeau and Frank and all the way to Leroy. It is that in any age, the geniuses are the ones absorbed in inventing a world that no-one else can see yet.

Like these articles ? Why not subscribe and enjoy 6 issues delivered direct to your door, 6 times a year. HERE

Like these articles ? Why not subscribe and enjoy 6 issues delivered direct to your door, 6 times a year. HERE